Despite the progressions that we have made today on women’s rights and gender equality, the conversations surrounding menstruation and female reproductive health are still considered forbidden in some spaces. Menstruation (also known as a period and many other colloquial terms) refers to the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina. The use of menstrual products, the difficulties in menstruation, and the overt disparities in women’s health are often kept out of the mainstream eye due to their “indecent” nature. Moreover, these norms are perceived to be obstacles that prevent discussions on menstruation and reproductive health.

Nevertheless, the advancements in science and technology have paved the way for the issues regarding menstruation to be outweighed by the improvements and solutions for menstrual hygiene and health. With a growing focus on how period products and the means of maintaining menstrual hygiene are changing, it is necessary to highlight the evolution of these products as well as their impact on women’s lifestyles.

On the rag in the 1800s

Historically, the development of menstrual products has always been dependent on geographical location, available resources, and cultural attitudes toward menstruation. Prior to the 20th century, menstrual blood was collected through a variety of materials across different cultures. In ancient Greece, small pieces of absorbent wool were wrapped around wooden splints and inserted vaginally. Similarly, the Egyptians in ancient times also utilized papyrus fibers in a parallel fashion, though the material was not able to absorb liquid. Mediums such as moss, natural sponges, animal fur, and textile scraps were also used as means of maintaining menstrual hygiene, and while they managed to collect the discharge associated with menstruation, these products were not the most comfortable nor the most effective.

By the turn of the century, from the 1800s to the 1900s, the concerns about bacterial growth from inadequate cleaning of reusable products between wears created a new market for menstrual products and hygiene. Women from societies across Europe and North America began using homemade menstrual cloths from flannel or rags, coining the term “on the rag” as a euphemism for a woman’s period. During this time, approximately 20 patents were taken out for the production of new menstrual products. Items such as rubber bloomers, sanitary aprons, elastic belts, and even the first-ever menstrual cups were produced in an attempt to appeal to women as an effective and comfortable alternative to the menstrual rag. Yet, regardless of the consistently expanding market for menstrual hygiene products, the stigmas attached to women’s reproductive health meant that consumers were still reluctant to be seen purchasing such products.

Code red on the battlefield

It was World War I that enabled the introduction of the very first disposable pad, primarily as a wartime necessity. The Kimberly-Clarke Company, a bandage manufacturer during the war, began mass-producing disposable pads, which were attached to a girdle-like device that was meant to hold the pad in place. Though they gained most of the recognition for introducing the idea of the disposable pad, much of the credit should be given to the field nurses, who, in the face of uncertain laundry facilities, frequent travel, and an abundance of manufactured surgical dressings, popularised the disposable sanitary pad. After using cloth bandages as a means to collect period blood, nurses noticed that cellulose was more effective at absorbing blood compared to regular cloth and began using wood pulp bandages due to their absorbent ability and cost-effectiveness.

The debut of disposable pads on the battlefield resulted in an influx of pads being produced on a commercial scale. Made by Johnson and Johnson, these pads were made in 1896 and sold to the North American market as “Lister’s Towels” or “Sanitary Napkins for Ladies.” However, during this period, menstruation was still deemed improper and unseemly in society’s eyes and was thus restricted from being effectively advertised within the market, leading to the product initially failing. The socially-imposed shame attached to menstruation and period products was so prevalent that when it came to actually purchasing these items, women had to drop their money into a box with a slot at the store just to avoid face-to-face interaction with the clerk.

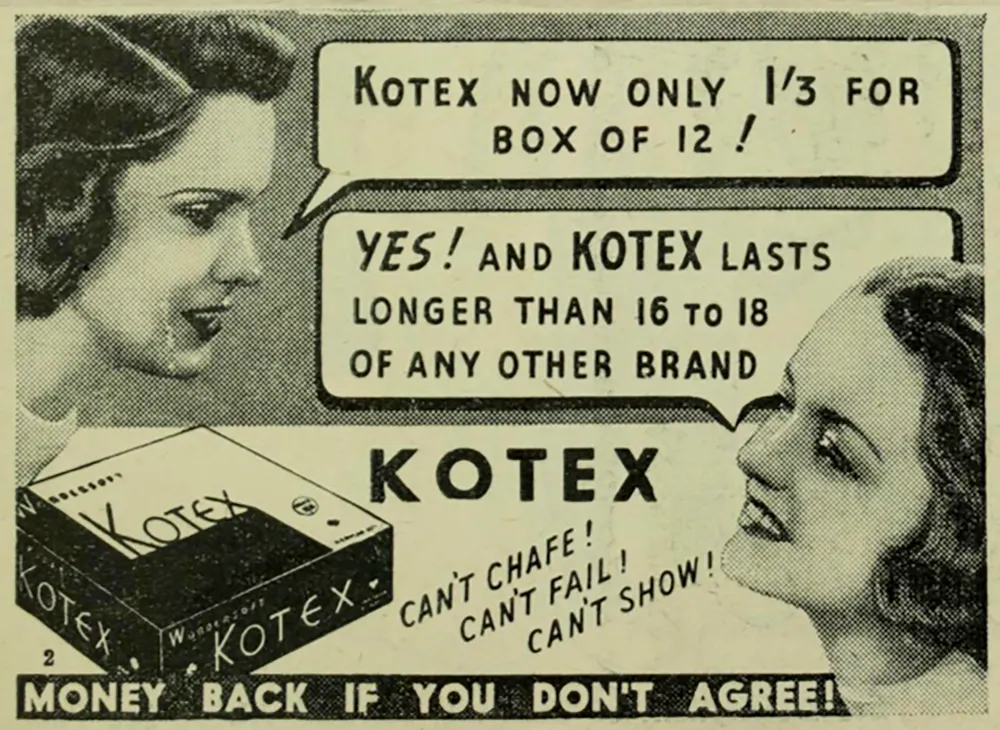

It was by the 1920s when these constraints grew more lax, leading Kotex to become the first successfully marketed sanitary napkin. Inspired by the disposable pads of the wartime era, these pads were made from the surplus of high-absorption war bandages and advertised primarily in women’s magazines. The innovations in the disposable pad provided a new level of comfort in maintaining menstrual hygiene for women and prompted the beginning of mainstreaming period products; women were now more in control of their autonomy and could participate in work and activities while being on their period.

Tampons for that time of the month

Due to concerns surrounding the close proximity of pads to fecal bacteria, disposable tampons became recognized as a healthier alternative to the disposable pad. However, there were still issues surrounding the use of tampons as many were unsure of how to insert them and whether or not it could cause the loss of virginity – a misconception that remains common to this day. This resulted in tampon package instructions emphasizing the difference between the urethra and the vaginal opening while simultaneously assuring wearers will not lose their virginity upon insertion.

Research found that upon adjusting and learning to insert tampons correctly, women were less likely to return to using disposable pads. Nevertheless, tampons carried a greater stigmatized burden than their substitutes, particularly in relation to virginity, masturbation, and their potential to act as contraception. Tampons in the early era were not as effective as pads as well; many reported them as being leaky, and consequently, the sale of pads overtook tampon sales. This resulted in greater improvements in the disposable pad; products were being developed with adhesive flaps, flexible sizes, and more discreet packaging.

However, this did not necessarily deter the demand for tampons. In the late ’90s, a massive health concern regarding synthetic tampons came to light with over 5000 reported cases of Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS), a complication arising from infection with certain types of bacteria. Yet, this health scare did not intimidate women from purchasing tampons; instead, it shed a greater awareness of the lack of government regulation over the safety and composition of menstrual products.

Cups for the crimson wave

Aside from the innovations in disposable pads and tampons, many were still searching for surrogate options for menstrual products. Items like genital deodorant and douching powders entered the market but failed to effectively appeal to consumers due to their formulas disrupting the natural pH of vaginas. In the midst of these products entering the market, the development of the menstrual cup gained significant attention due to its durability and for possessing benefits similar to the tampon. Initially, menstrual cups were made from aluminum or hard rubber, which were then inserted into the vaginal canal to collect menstrual blood. Similar to the tampon, the menstrual cup came under scrutiny for issues surrounding insertion and virginity, which were concepts that were deemed taboo in some cultures.

It was in the ’70s that the menstrual cup gained notoriety due to being linked to the second-wave feminist movement; women were becoming more comfortable in their bodies and adopting free bleeding – the practice of intentionally menstruating in public without blocking or collecting the period flow. However, this led to a number of health concerns. Residual blood left on surfaces have to be treated as potentially infectious as several viruses, including hepatitis, could live in dried blood for as long as four days. To avoid such issues, many women found the menstrual cup as a feasible solution to continue free bleeding while protecting their reproductive health.

The menstrual cup was also a popular choice in period products due to its cost-effectiveness and compatibility with the environmentalist movement, thus resulting in more and more women shifting towards using the cup instead of disposable products. With the progressions in health and science, today’s menstrual cups are now produced using medical-grade silicone that contributes to the prevention of infections as well as the promotion of female reproductive health.

Sustainability during shark week

With the increasing attention on climate action and adopting greener practices, many organizations have begun to incorporate sustainable components to appease their environmentally-conscious consumer base. The cloth pads from the 1800s were reintroduced to the market, this time with the integration of modern technology and resources, and as a result, were less prone to the growth of bacteria and more eco-friendly, all while still possessing the benefits of the mainstream pad. Tampons also took to the change and began being produced using organic material that aligned with the green movement. In addition to the improvements in existing menstrual products, the attention on sustainability also sparked the development of period-friendly attire and accessories. Period underwear and menstrual discs started to increase in popularity, and around the world, women were faced with consistently growing options and alternatives to managing their periods.

These new products enabled a greater market acceptance towards diversity and inclusivity; more period-related products and ad campaigns were shifting attention from the “delicate, white woman” to the varying body sizes of women, non-binary and trans folk. The stigmas surrounding menstruation have also mostly dissolved on a commercial scale. As the ads that refused to acknowledge menstruation as a whole are changing their focus to not only women’s reproductive health and the issues surrounding it today but also period positivity, sustainability, and environmental awareness.

Read also:

The Massaru Tax – Period: An Interview With Shafa Rameez

Period Poverty: Tax On Periods?

Period Shaming Has Now Become Mainstream